After Keir Starmer’s audacity in interpreting the phrase “defund the police” as meaning “defund the police” he has once again flipped his position and said he will sign up for “unconscious bias training” (or UBT) to make amends.

As is the way with these things, everyone is now wondering what UBT actually is. Coincidentally C4 have recently broadcast a programme titled “The School that Tried to End Racism” where a class of 12 year old children at a south London state school are subjected to a type of UBT. So we have a unique opportunity to witness what Sir Keir will be undertaking shortly in pursuit of his mea culpa moment.

At the opening of the programme we are told by Dr Nicola Rollock and Prof Rhiannon Turner that the pursuit of “colour blindness” is not only unproductive as an attempt to end racism, but is actually itself racist. The logic being that to ignore someone’s race is to also discount their culture and “lived experience”. This requirement of having one’s “lived experience” recognised is not reciprocal though, it seems, as later in the programme while watching the white students struggle to define what “being white” means, Rollock states “we don’t think about white people having an identity or a culture”.

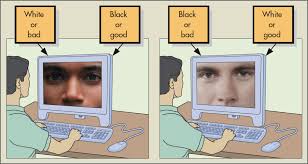

To start their UBT, the children take the “Implicit Association Test” (IAT) which was developed in the late 90’s and purported to measure biases that people are unaware they harbour (in this specific case, racial biases) [1]. The test is presented to the children as being flawless and the results are declared with no caveat on accuracy or interpretation beyond a very crude declaration; the class has a majority bias in favour of white people.

But is the IAT really that accurate? I don’t intend to delve into it fully here and, to be honest, others have written extensively and much better than I could on just how flawed the IAT is in terms of measuring implicit bias. However, for the purposes of discussing what follows in the programme we should outline two key points. Firstly, those taking the implicit bias test can get different results each time, even on the same day [2]. It is quite likely, therefore, that were the children in the programme to take the test immediately after, later in the day or later that week, the results could be different. This raises important questions about the validity of the test at all.

Secondly, there have been several studies that find no predictive ability between measuring “implicit bias” in someone and their prejudices [3]. So we have a test that isn’t accurate, which no-one can ascertain quite what it is measuring and that has no predictive power. This is a point worth making because the results of the test are used within the programme as the basis for everything which follows in the UBT of the children.

Back to the show and next we are presented with the challenging scene of the class being racially segregated into two “affinity groups”; those students identifying as “white” in one and those as “non-white” in the other. Rollock and Turner make little attempt to hide their pleasure at seeing the white students become visibly uncomfortable with this part of the process (one student later recounts the experience to his parents “If I had the choice I would be with my friends, not [separated] by race because that feels awful”). Rollock and Turner explain that they are pleased by the white students being upset as it is exposing them to the feelings of “being excluded”. It is not clear that the non-white students have had this experience within the school and the opening of the programme conversely showed that the pupils chosen for UBT were well integrated and did not consider race as a reason for exclusion.

Why the white students must now be shown what “being excluded” feels like due to the results of IAT is expanded on by Turner who, in discussion with Rollock, makes the claim that “white kids aren’t affected by systemic inequalities” (Rollock agrees). Later, these inequalities are further described by Rollock as being prevalent in everything (thus the use of “systemic”, I assume) but specific examples are cited as inequalities in the justice and education systems.

This is something I covered in a recent post and it is perhaps worth noting again here that in many instances the statistics pointing to these inequalities either don’t give a clear indication that “systemic racism” is to blame (the problem is much more complicated than simply answering “racism”) or, in some cases, totally contradict the theory that a “white supremacist” system is at play.

Considering the nature of the programme, education inequality is quite an apposite issue to look at and Rollock’s reference to racial disparities within the UK are true, but not as she presents them. Indeed, the case is quite the opposite. White boys from disadvantaged backgrounds are by far the poorest performers within the education system. White working-class boys are 40% less likely to go into higher education than their black counterparts. Of those that do, 9% will go to university, compared with around half of the general population. In short, Rollock is completely wrong here and it is worth remembering that this flawed reasoning is being used to justify causing considerable upset and distress to these children.

Probably the only part of the programme that was a pleasure to watch was when the children were invited to bring in items and discuss their heritage/culture. It was uplifting to see what happened when the children were left to interact in this way and conduct honest lines of inquiry into each others backgrounds. But it left one wondering what the point of the previous segregation was, other than to purposefully upset. Could this exercise of coming together to share cultures not have been conducted without the prior IAT?

Are we to believe these children would have reacted negatively unless they were first told they were unconsciously racist? It seems unlikely considering all of the children were well integrated from the beginning and, during the segregated “affinity group” meeting the white students all expressed concerns about making comments less they make “a mistake” and are accused of being racist. Indeed, just after the IAT one student voices a genuine concern that, were they to “fail” the test that the system would report them to the police (Rollock and Turner find it amusing that a child is worried about being reported to the authorities for having implicit racial bias). None of this suggests the children would be unreceptive to sharing cultural backgrounds and insights without the IAT and “affinity groups” being conducted first.

At the end of the programme a class exercise is conducted whereby all the children line up at the start line for a race. However, the children must adjust their position relative to the start line (one step forward or one step back) depending on their response to various questions. Turner explicity states that the questions are selected to demonstrate the “white privilege” which she says affords the white students an unseen advantage. The questions posed include things like “have you ever been the only person of your race in a room?” and “is English your parent’s first language?”. Not surprisingly by the end of the questioning the class is distributed such that most of the white students are ahead of the start line while most of the non-white students are several steps behind. Considering Turner admitted prior to the exercise that the questions were designed to produce this result, this is hardly surprising. Never the less, the students are told this is a clear demonstration of the racial bias operating within society. The students are understandably shocked at the apparent injustice. The non-white children express irritation and obvious resentment at the unfairness and the white children struggle to offer more than awkward, guilt-ridden agreements at the unfair advantage they have been given.

But what other questions could realistically be asked to illustrate positions of “privilege” in terms of life chances? What about “take a step forward if you are naturally good with numbers”, “take a step forward if you find it easy to make friends” or “take a step backward if you find it difficult to learn something without assistance”? Do these abilities provide advantages or to use the vernacular “privilege” in society? Undoubtedly and demonstrably via the research literature, yes, they do. And they have nothing to do with race.

What to make of any/all of this? I won’t re-iterate my criticisms of the programme above as I think they are pretty clear, but we should take a moment to look at UBT as a viable method of reducing racism at all, as well as the implications for its use in schools without public consultation.

Firstly, we must note that UBT usually hangs on the presuppositions that the IAT is a) capable of measuring implicit bias, b) measures it accurately/reproducibly and c) a predictive tool for someones unconscious biases which an individual will display. As discussed above, it has been shown that the IAT is neither reproducible or having any predictive power [3] and that it cannot even be said with confidence exactly what it is measuring [2].

It may come as no surprise to learn, therefore, that there is some disagreement (even among proponents of the IAT) as to whether UBT works at all in terms of altering implicit biases or behaviour [4] [5]. Indeed, since the IAT itself is not reproducible it is questionable how one could demonstrate a change in something like implicit bias if it cannot be measured.

This is just the first episode of a two part programme (I am yet to watch the concluding part) but it has already been revealed that the finale will be a re-take of the IAT by the class. Undoubtedly the result will be a lessening of the supposed bias discovered in the initial test (or a total remission), UBT will be deemed as a success and a question will be posed about rolling UBT out across schools nationwide.

We must be clear here. The implications of applying UBT and this critical race theory mode of analysis to children are not inconsequential. By their own admission in this programme, academics like Dr Nicola Rollock and Prof Rhiannon Turner have the intention of forcing children into analysing the world (or more accurately everything) along racialised lines in order to, they believe, reduce racism.

The argument can be made that if the effectiveness of the IAT is demonstrably nil and UBT itself is doubted in terms of achieving the goal of reducing racism, then there must be a full and open public discussion before we proceed with racialising the nation’s children. The risks are all too real that we could take happy, integrated school children and fill them with guilt, mistrust, envy and resentment.

References

[1] “Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. – 1998

[2] Blanton, H., & Jaccard, J. (2008). Unconscious racism: A concept in pursuit of a measure. In K. Cook, & D. Massey (Eds.), Annual Review of Sociology (pp. 277-297). (Annual Review of Sociology; Vol. 34).

[3] Forscher, P. S., Lai, C. K., Axt, J., Ebersole, C. R., Herman, M., Devine, P. G., & Nosek, B. A. (2016, August 15). A Meta-Analysis of Procedures to Change Implicit Measures.

[4] Atewologun, D., Cornish, T. and Tresh, F., 2018. Unconscious bias training: An assessment of the evidence for effectiveness. Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series.

[5] Noon, M., 2018. Pointless diversity training: Unconscious bias, new racism and agency. Work, employment and society, 32(1), pp.198-209.